begann das drama 1995? / reserveanforderungen!

ich kann euch versprechen das sich obwohl der text ziemlich lang und auch teilweise etwas komplizierter ist sich das lesen in jedem fall lohnt. ich habe hier ne menge neue sachen gehört die mir so noch nicht bekannt waren. wirklich ein wahnsinnbericht. ein grund mehr warum ich mit meiner goldposition und dem $short mehr als wohl fühle.

das ganze klingt erneut logisch. da dies für mich aber eher neuland ist habe ich miener überschrift mal vorsichtig ein ? gesetzt. ausserdem weiß ich leider nicht inwieweit die ezb ihre reserveanforderungen ebenfalls modifizeirt hat um jetzt ausschließlich zur fed zu zeigen. china hingegen hat gerade erst die letzten wochen die reserveanforderungen noch oben angepaßt um der kreditvergabe herr zu werden. kann mir bei der ezb ebenfalls nicht vorstellen und schon gar nicht bei der seinerzeit am hebel sitzenden bundesbank das die ähnlich "großzügig" oder besser "fahrlässig" gehandelt haben wie die fed.

dank geht an ituillip und aaron crowne!!!!!!!!!!!!

http://www.itulip.com/forums/showthread.php?t=292

What (Really) Happened in 1995?

How the Greenspan Fed Screwed Up in the Mid-90s and set the stage for the Greatest Financial Bubble in the History of the World.

by Aaron Krowne

A Sleeper Year

1995 was, by any reasonable accounting, an unremarkable year. Can anyone remember anything significant that happened in 1995? I sure can't.

We were coming up on an election year, but Clinton was pretty much a shoe-in, as the Bush I Republican administration had squandered a wartime presidency, ending on a sour economic note. The administration was widely perceived as an economic failure, buoying Clinton's first term by contrast. But other than that, not much happened.

The internet craze hadn't arrived yet, peace seemed possible in the Middle East, oil and gas were reasonably priced, and the previous recession and bad housing market were fading fast in the public's collective memory. The usual metrics of economic health -- GDP, inflation, wages, employment -- all showed improvement; nothing spectacular, but economic indicators pointed to good progress that was due to extend well into the future.

Life was good. Optimism reigned.

But something strange did happen in 1995, while all of this good livin' was going on.

Good as Gold

I first suspected that something was amiss earlier this year, when I read an interesting article by Don Luskin entitled Good as Gold. The article came on the tail end of the Greenspan-Bernanke transition, while the economic and financial markets zeitgeist was still awash in Greenspan hagiography. To me, Luskin's article was a welcome bucket of well researched, analytical cold water on the over-heated rhetoric about the great job Big Al did in his 18-year tenure.

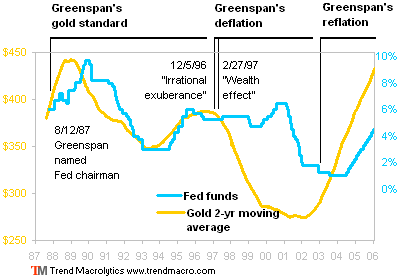

What Luskin said was that the formula for Greenspan's success, as well as his later failure, was the simple rule that the Fed's behavior should mimic a gold standard, despite the fact that there is no such official standard in our purely fiat-based currency system. Specifically, the Fed under Greenspan was apparently shadowing the price level of gold [Figure 1] in setting interest rates. This was the real reason for Greenspan's excellent, often counter-intuitively good performance until 1995; he had raised rates when the conventional wisdom said to drop them, and vice versa, and had "proven" the conventional wisdom wrong.

Figure 1: Interest rates and the gold price level. Note the behavior change after 1995

Greenspan's approach was obvious to many gold-watchers, and some commented on it at the time, but things get interesting in 1995 through 1996. In this time frame, Greenspan broke from following the gold price level, raising rates higher and keeping them high for a few years. This is when things started to get out of hand, and the asset bubbles familiar to iTulip readers -- stocks first, then real estate -- began their ascent. Greenspan had stopped following his own formula, and, as Luskin said, "the global economy went haywire.''

Clearly Luskin was on to something. But exposing the shift in Greenspan's monetary modus operandi raises more questions than it anwers. Why did Greenspan break from his own virtual gold standard formula? Why did an asset bubble follow from an increase in interest rates? And, most perplexing, Why did the broad measure of the money supply as measured by M3 begin to soar at that point? (paßt irgendwie nicht zusammen, oder ?, die auflösung ist wirklich spektakulär)

As Luskin points out, the shift occurred precisely during the period where Greenspan began to worry aloud about "irrational exuberance." Clearly Greenspan was trying to pre-empt some major disaster he foresaw with some "tough love.'' Was there some risk in his view that was servere enough to cause him to suddenly abandon his proven, tried-and-true formula?

On the last question of M3, one must see it [Figure 2] to believe it. As the historical picture of M3 spanning 1995 shows, M3 expanded like mad starting in 1995.

Figure 2: Historical level of USD broad money supply (M3).

(leider kann ich den chart nicht zeigen) der chart zeigt aber ne klare linie von links explosionsartig gen norden (zahlen unten)

money supply (m3) 1995: 4 trillion 2000: 8 trillion 2005: 11 trillion

There are clearly two eras here, as iTulip.com pointed out in the Frankenstein Economy: before 1995 to 1996 and after.

After 1995, the broad money supply exploded, and it has never looked back. Asset bubbles and inflation -- mostly one, then the other -- as a consequence are surprising only to those who do not understand basic economic principles of supply, demand, and the psychology of market participants as explained by the school of economics called "Austrian Economics." Unfortunately, most economic and market professionals and commentators do not and consider the Austrian school outdated and unorthodox.

There were other signs that something fundamental changed in 1995. I have for quite some time seen anomolous behavior in economic data beginning in 1995, from various sources. One example is Econbrowser post M3 or not M3? where Menzie Chinn defends the elimination of M3 reporting by looking at the coupling of M3 to M2 and the GDP. His own charts show that the relationship, and his arguments, break down around and after 1995, and he has no explanation for this. An argument against ending M3 reporting and providing an alternative is available in this excellent NowAndFutures.com article.

So what changed in 1995 that messed up Greenspan's game and distorted the economic data?

The Fed and the Reserve Fraction

Very few people realize that in the early-to-mid 90s there was a core change in the functioning of the Fed and the dollar-zone economy that precipitated the massive rise of M3 and the various associated asset bubbles. This core change was amplified by a couple of other simultaneous trends, which I will also discuss, and caused a number of secondary ills. But first I will explain the central piece of the puzzle. First, a brief background on fractional reserve banking is required.

The banking system in the US is a fractional reserve central banking system. One can read about this in more detail at the link supplied but the gist is that banks are required to keep a fraction of their assets on hand, deposited safely at the Fed, to act as a "cash cushion'' at times when depositors demand their money from the bank as cash. This cash reserve is in proportion to the amount of depositors' money that is loaned out. The proportion of this cash reserve to the total amount loaned out is intended to provide just enough of a buffer to keep the bank solvent and keep things running smoothly in the event a lot of depositors make demands for cash at once, such as during a run on the bank. This fraction, called the reserve fraction (or ratio), is typically from 5% to 20% of the amount of money the bank has loaned out. This may seem low, but holding any more cash in reserve than is needed except for outlier cases is considered an uneconomical use of capital by a bank. The cash in reserve is not making money for either the bank or its depositors as loans, so from a day-to-day operations persective, the less reserves the better. From a longer term risk management perspective, the more the better. Statistically, 5% to 20% reserves is the "right" amount, except in those outlier cases where these levels are either too high because reserves at those levels are at some times constraining the economy's access to credit or, conversely, too low at other times because too many depositors are making a rush to liquidity and demanding their cash.

The reserve fraction, considered as a number that is mutable as a matter of policy, is also one of the most powerful tools a central bank can use to adjust the amount of money available to the economy. It is easy to see why: a reserve requirement of 10% means that banks can lend out ten times the actual money on deposit with the fed. Even a seemingly small change from, say, 2% to 8% means that 12.5 times the money on deposit can be lent out. For example, $10bln initially on deposit with a 10%, reserve requirement results in approximately $100bln of money available as loans. If the reserve fraction is reduced from 10% to 8%, the for the same $10bln cash on deposit there can be approximately $125bln of money available as loans in the economy. This is an increase in the money supply of around 25% from a reduction of the reserve ratio by 2%. (die auflösung!)!!!!!!!!!!!!

Austrian Economists have objected to this system for years, pointing out, as Rothbard did in his tract "The Case Against the Fed,'' (Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn, Alabama, June 1994). He argues that a bank using a fractional reserve is by definition an inslovent bank. I agree with this point, but the purpose of this article is not to debate the legitimacy of fractional reserve banking. The objective is to show that what happened starting around 1995 is much worse than even the most blistering theoretical critique predicted. It is a veritable nightmare scenario that we all will have to cope with for years to come.

The key event that happened around 1995 is that the fractional reserve ratio was not only lowered, it was effectively eliminated entirely. You read that right. The net result of changes during that period is that banks are not required to back assets which largely correspond to M3 or "broad money'' with cash reserves. As a consequence, banks can effectively create money without limitation. I know that sounds hard to believe, but let's look at the facts.

Imagine if the limit of the amount of money in the banking system was not, as in the above example, $125bln, but was effectively infinite for the same $10bln on deposit. Further, imagine that this change in banks' ability to create loans coincided with new and exotic forms of money being invented via the securitization of debt and extended to entirely new asset classes and made available to a far larger range of people that previously did not qualify for loans. This essentially describes our system today.

If this sounds like a bad idea to you, even if you are not an expert in banking and finance, you can give yourself a gold star for having a good intuition, because this arrangement is not only bad, it is catastrophically bad.

Behind the Curtain

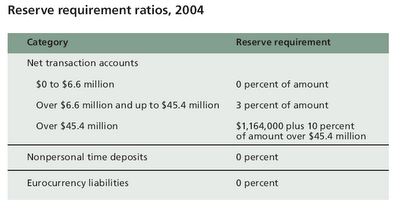

I know this sounds hard to believe but I don't expect you to believe the claims above without clear evidence. For this I refer to the Federal Reserve itself. As you can see in the Fed's document at this link, the changes that led to an effective elimination of reserve requirement actually began in the 1990-1992 era. Likely in response to the recession at that time, the Fed decided to relax reserve fraction requirements in the manner quoted below. The resulting table [Figure 3] is shown here:

Figure 3: The Fed's reserve ratio requirements (current rules, 1992 through 2004 to present).

Predictably, when these changes were made, total cash reserves in the banking system dropped sharply. The economy liquefied nicely, and we came out of the recession relatively quickly, just not fast enough to save Bush Senior's hide.

It may surprise you to learn that, as the table above reveals, there exists a 0% reserve class of money, and we'll return to this later. For now, let us see what the Fed had to say about these 1990-1992 changes (my emphasis):

Following the passage of the MCA in 1980, reserve requirements were not adjusted for policy purposes for a decade. In December 1990, the required reserve ratio on nonpersonal time deposits was pared from 3 percent to 0 percent, and in April 1992 the 12 percent ratio on transaction deposits was trimmed to 10 percent. These actions were partly motivated by evidence suggesting that some lenders had adopted a more cautious approach to extending credit, which was increasing the cost and restricting the availability of credit to some types of borrowers. Apparently banks taking care in extending credit was a scourge that had to be eliminated, and the Fed stepped right in to "fix'' the problem by opening the spigots of liquidity. Certainly its a bad sign if your central bank considers prudent lending an ill and acts against it; but something even more insidious happened over the next few years.

From early 1994 to late 1996, most of the remaining reserve deposits disappeared. This is visible in the following chart [Figure 4], again, from the Fed.

Figure 4: Reserve ratio required deposits through the 90s, and contractual clearing balances.

You can see the sharp in reserve balances 1990/1991 as the statutory reserve ratio requirements were lowered. Then reserve balances gradually increased until 1994, presumably, as the economy grew and demand for money with it. But then the trend dramatically reverses and reserve deposits head downward through 1996. The Fed has an explanation for this on page 44 of the same document (again, my emphasis):

You can see the sharp in reserve balances 1990/1991 as the statutory reserve ratio requirements were lowered. Then reserve balances gradually increased until 1994, presumably, as the economy grew and demand for money with it. But then the trend dramatically reverses and reserve deposits head downward through 1996. The Fed has an explanation for this on page 44 of the same document (again, my emphasis):

Although reserve requirement ratios have not been changed since the early 1990s, the level of reserve requirements and required reserve balances has fallen considerably since then because of the widespread implementation of retail sweep programs by depository institutions. Under such a program, a depository institution sweeps amounts above a predetermined level from a depositor's checking account into a special-purpose money market deposit account created for the depositor. In this way, the depository institution shifts funds from an account that is subject to reserve requirements to one that is not and therefore reduces its reserve requirement. With no change in its vault cash holdings, the depository institution can lower its required reserve balance, on which it earns no interest, and invest the funds formerly held at the Federal Reserve in interest-earning assets.

When banks wanted to expand their lending, they found a technical workaround using "retail sweep programs.'' How innovative! Apparently, the Fed approved of all of this, too, apparently losing sight of the reason we have reserve ratios in the first place.

What was the result of these two changes, the creation of classes of zero and near zero reserve ratio accounts and the ability of banks to move money from accounts with high reserve requirements to accounts with low or now reserve requirement?

A flood of free money.

There was then almost no limit to the promissary notes, in the form of various securities, that could be created by banks -- with fees of various sorts -- interest, originating fees, maintenance fees, penalties, and so on -- collected all along the way and booked as profits. This transformation of banking practices seems to have started small, but really picked up steam by 1996 and 1997, likely due to competitive pressures among banks; those banks that used these methods could easily out-compete those that did not. Even if some banks avoided these practices for a while because they thought them too risky, eventually they were forced to play along or risk losing business to banks competing for the same borrowers.

But wait, as they say on late night TV, there's more!

Apparently, some banks ran into a hitch even within this new liberalized scheme: they couldn't completely avoid the reserve fraction requirement. For reasons that are not discussed in the Fed's document, banks were still required to keep some money in reserve corresponding to these new accounts in order to fully access the Federal Reserve system. Perhaps there were bitter protests behind the scenes, where us mere taxpayers and wage-earners aren't allowed to look, because later the Fed came up with a new change: new requirements for contractual clearing balances, that second line in the Fed's chart above.

"What the heck are contractual clearing balances?'' you ask. These are not explained in detail, but the Fed mentions on page 45 of the document why they were implemented:

The rise in contractual clearing balances during the 1990s did not match the decline in required reserve balances, however, in part because depository institutions apparently did not need as large a cushion to protect against overnight overdrafts as was once provided by their required reserve balance. In addition, the ability of some depository institutions to expand their contractual clearing balances was limited by the extent to which they use Federal Reserve priced services.

What the Fed is saying is that some banks couldn't access the Fed's system because of remaining restrictions in the reserve requirement, and things were running okay anyways, so they simply made new rules that said that only a smaller amount of money proportional to the amount being immediately processed needed to be held on deposit at a Fed Member bank. This is in contrast to having an amount of real reserves proportional to the total holdings of the bank.

With this change to contractual clearing balances, a final barrier was lowered: now banks had full access to the Fed system based on a lax set of reserves rules that effectively omitted any meaningful anchor of loans growth to cash reserves. Considerations of solvency during times of crisis and limiting money creation took a back seat to bank profits and money expansion.

Effects

This certainly goes a long way toward explaining a number of observable phenomenon, such as soaring M3, the stock market bubble, real estate bubble, and surprisingly strong banking and financial sector profits, even through a number of severe challenges to The System, such as the Asian Financial Crisis and 9/11.

Since circa 1995, with reserve requirements effectively eliminated as a policy lever to control the money supply, and interest rates already high, the Fed found itself unable to exercise much influence over the economy. Recall that the reserve fraction has a direct and outsized impact on the money supply, while short term interest rates are set by the Fed via open market manipulations and these only change the money supply at the margins, sufficient only to alter the price of Treasury securities or, equivalently, their yield. This dynamic helps explain why in the last decade some observers have correctly posited that the Fed's control via interest rates has been waning. Thus, Greenspan's pre-emptively "high'' interest rates had little effect on the money supply and the asset bubble that he likely saw coming his way. Or perhaps, worse than doing nothing, these rate hikes seem to have done the opposite of what was had intended.

At the same time Greenspan was getting "medieval'' on the market, Japan was going weak at the knees. In an attempt to coax its economy back to life after a half-decade of recession, through 1995 the Bank of Japan dropped interest rates from 1.75% to .5%, an action historically unprecedented, which effectively made that country's interest rate zero.

Well, in a world of very mobile capital between developed countries and no limit to paper money creation in the largest of them, hundreds of billions of dollars exited Japan for US shores, in search of a higher interest rate in a process known as global basis-point arbitrage. To make matters worse, third parties began borrowing in Japan and investing in the US at a higher return, and the yen carry trade was born. Hedge funds would later greatly multiply the effect of this phenomenon. Like a giant vacuum cleaner, the US had sucked up much of Japan's free capital, likely exacerbating Japan's recession instead of alleviating it. As my good friend Jameson Penn has observed, all that was left in Japan after this setup was "the dumb money," not exactly conducive to a domestic recovery.

This all helps explain the anamoly of the strong dollar of the mid-to-late 90s, and the accelerating death of the US manufacture-for-export sector. It also probably has a lot to do with the soaring fortunes of the ultra-rich, in contrast to the inflation-caused flat-to-declining real wages of most everyone else, as discussed in The Modern Depression. With the observation of the changes made to reserve requirements and rules for qualifying accounts, it looks like we can close the book on questions about those two trends.

But, unfortunately, there's even more. The Fed probably made another serious mistake: manipulating the price of gold as documented by Cheuvreux investment analyst Paul Mylchreest. If the allegations are correct and the Fed led or participated in a global central bank game of "short-selling'' gold via "bullion bank'' lending, then the Fed was de facto suppressing the price of gold. So what's wrong with that?

Recall that Greenspan was especially successful, as Don Luskiin pointed out, until 1995 because he ran Fed interest rate policy based on the price of gold, on a virtual gold standard. Perhaps he wasn't aware of everything that was going on at the Fed, and some elements at the Fed conspired to drive the gold price down to make the dollar -- and by extension, the Fed -- look better, without his knowledge. Or Greenspan was all too well aware of these manipulations, and this is why he stopped using the gold price to guide interest rate decisions in 1995; the price started to fall then due to these manipulations and he knew the gold price was no longer a reliable, free market indicator of inflation and the money supply.

The upshot of all of this is that the price of gold, even when manipulated, may be acting as a proxy for the neutral rate a good proxy for the neutral rate; that is, the imaginary, "natural'' rate of interest at which the central bank is neither encouraging nor discouraging growth. Some call this the "equilibrium rate,'' but don't let any Keynesians hear you say that. By mucking with the price of gold, the Fed would have been adding fuel to the fire by making the fiat interest rate diverge even farther from the neutral rate.

The ultimate result of anomalously high interest rates and economic growth was to draw even more global capital to the US system, as the rest of the world scrambled to take advantage of the "great deal'' this presented. If memory serves, a key fuel for the tech bubble was corporate bonds, which must have seemed like a truly amazing deal compared to interest rates on comparable bonds in Japan or the neutral domestic rate.

Conclusion

The specific changes in Fed policy discussed in this article are no less than an abrogation of the Fed's responsibility to manage the money supply of the United States. The Fed's behavior has been a crime visited upon the general citizenry, and the impact of the resulting asset bubbles and inflation will eventually be recognized as harming the most vulnerable the most severely. And for those that don't believe broad money-supply increases inevitably lead to long-run inflation, The Economist has bad news for you:

Figure 5: Think broad money has nothing to do with inflation? Think again

The Fed did indeed learn something from the Great Depression: never reduce the money supply drastically, and especially, don't let the inflation rate fall below zero. The chaotic behavior of the global financial system even after this "lesson'' was learned suggests to me that this fundamentally command-based economic institution will always find a new way to screw things up. As this article shows, when working, all the Fed does is mimic non-fiat based monetary system, such as the gold standard. When the current fiat money regime is not working, it is doing everything but that. With a nearly infinite number of ways to screw up, and subject to the short-term interests of Wall Street and politicians, but only one way to succeed -- it imitate the gold standard -- suggests to me the Fed is not only not helpful to the economy, but harmful.

I predict that, after a major collapse of the dollar based fiat money system that wrecks the dollar economic zone, the Fed will be replaced with either, 1) a new sound-money currency and competitive banking system, or 2) a super-national American central bank, presiding over a North American "New Dollar Zone,'' analogous to the Euro Zone currently and the recently proposed Asian Currency Zone. The international community will decide that no one country can manage monetary policy that determines the fate of a significant proportion of global capital and investments. Signs that an economic federation can do better are already visible in ECB policy of limiting broad money growth to control long-run inflation, a principle the Fed explicitly and ideologically eschews.

After the US economy shrinks to a more globally proportionate level, it will probably be unable to sustain trade or attract investment at close to current levels until it chooses one of the above methods to ensure the soundness of its currency and thus convinces the rest of the world again that a significant portion of their wealth can be invested safely in the US.

wow! im prinzip hätte die fed also auch die auswüchse der letzten jahre wohl relativ leicht begranzen können in´dem sie mal flagge gezeigt hätte und einfach mal ein bißchen diedaumenschrauben bei den reserveanforderungen anzieht. ganz abgesehen davon das sie die kreativen fianzierungen niemals hätte zulassen dürfen. jetzt haben wir den salat.

gruß

jan-martin

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_euoz_2.gif)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home