Danger—Explosive Loans / another credit innovation

as often mentioned the main driver of the markets is and has always been "liquidity". the easiest way to reach this goal is a liquid (and that means also cheap) credit market. over the last years there has been a wave of new "innovations" in the credit sektor (mbs, cds, etc...). every single innovations has pumped up the liquidity more and more. you really ask yourself "what´s next?"

dank geht an mish http://www.markettradersforum.com/ plus business week die einmal mehr kritischer als andere sind! hut ab!

Collateralized loan obligations offer loads of cheap money. But payback time may be coming http://tinyurl.com/y5u28z. highlights:

while market watchers have spent the past few years wringing their hands over hedge funds, CLOs have become an even more integral part of the financial system--and just as worrisome.

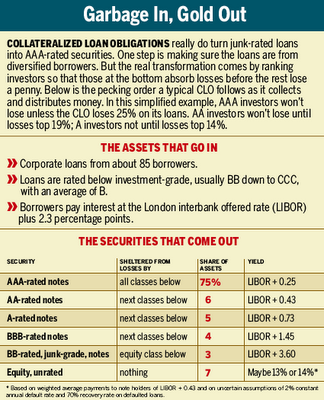

CLO managers essentially buy a bunch of loans arranged by banks, package them together into a pool, and then carve out different securities to sell to investors, taking a fee for their troubles. While the loans they collect are mostly "junk"--meaning they carry low credit ratings--the securities that come from the pool are mostly "investment-grade," carrying high ratings. Ironically, that attracts people seeking the very safest investments.

But can you really squeeze that much safety out of that much risk? The idea is that the risks are so dispersed that most investors end up doing well. Yet there's something akin to a perpetual-motion machine at work here. How long can it go on?

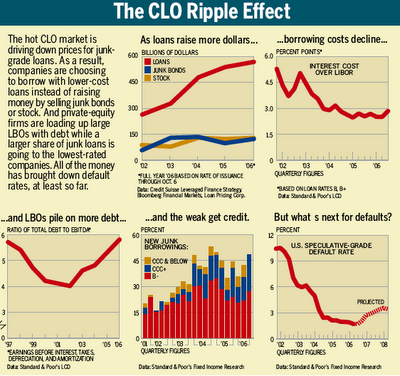

Now CLOs are doing the same for the $500 billion commercial lending market. They're making capital cheaper for companies, lowering the risk for lenders, and, so far, providing investors with enviable returns.

CLOs are powering two other arenas, too: the private-equity business, which counts on them for financing, and the $14 trillion stock market, which has been propped up recently by furious buyout activity. Without CLOs, leveraged buyouts like the record $27 billion deal for hospital operator HCA Inc. wouldn't be happening on such a grand scale.

Wall Street is pushing CLOs with full force. Year to date, CLO managers have gathered in $90 billion, double last year's pile at this point, which was double the year before that.

In fact, unbeknownst to many, CLOs are pumping up the entire U.S. economy. By lowering borrowing costs and attracting foreign capital, they're helping to keep a lid on interest rates

Innovations like CLOs are a big reason why. They've kept the gears of the world's biggest economy so well-oiled that foreign investors can't help but be attracted to it.

But while financial innovations fuel booms, they also tend to worsen busts. Wall Street's lack of willpower is legendary. The pattern goes like this: Come up with a brilliant idea, nurture it until it catches on, then flog it until it breaks

CLOs are financing dicier endeavors all the time. They've encouraged companies to take on more floating-rate debt, which could cause problems like those now being felt by homeowners who took out adjustable-rate mortgages a few years back. CLOs also have encouraged companies to put up more of their assets as collateral for lenders, which during hard times could hinder their financial flexibility. And CLOs' successes so far have lulled investors into a false sense of securit

CLO managers are using financial engineering techniques dating back to the emergence of junk bonds

By 2002 the structures were being designed well enough to rekindle corporate lending after the telecom bust

Their ingeniousness allows them to haul in more money from investors than Wall Street could raise with an army of its finest salesmen. Essentially, the devices vacuum up junk-rated leveraged loans and, voilà, turn out investment-grade notes. Think of a CLO as an upside down pyramid in which a few people at the bottom support many at the top

Recently CLOs have been collecting yields from their loan pools about 1.9 percentage points greater than the yields they're paying on the rated notes they've issued. The difference goes to investors holding the unrated securities issued by the CLO; it's the premium they get for the risk of losing everything if the loans go bad. "It is highly levered and has the risk that it will just blow up totally. Similar structures, all coming under the heading of collateralized debt obligations, are being deployed to funnel billions into home mortgages and derivatives on investment-grade corporate debt.

TRIPLE-A DEMAND

By carving up the loan pool into different risk levels, CLOs have been able to corral billions of dollars from insurance companies, pension funds, and ultrawealthy individuals around the world who crave AAA-rated investments and nothing less--certainly not loans to fund LBOs

SHAKY FOUNDATION

The immediate concerns are loans to auto industry suppliers, homebuilders, and suppliers to the homebuilders. Homebuilders alone account for about 5% of loans outstanding, big enough to matter but small enough not to panic the bulls.

Ultimately, loans made for LBOs could cause the most trouble

Worrisome signs are mounting. The amount of leverage used in deals right now is greater than the previous record set in 1997

At the same time, loans are carrying lower ratings, with fewer safeguards, than at any time since the late 1990s. The worse mix suggests that in a recession on the order of the one in 1991, default rates would soar more than four percentage points beyond the record 12.8% set that year

CLOs are accepting more so-called second-lien loans. Like second mortgages, these are backed by borrowers' assets, but their claims on that collateral come second. "Second liens could be the potential Achilles' heel of the current credit cycle

Fundamental credit analysis of borrowers' ability to repay loans is being shortchanged. In other words, investor diligence has been less than due: A pool of 85 diverse loans may look good by the rating agencies' statistical and historical models but still hold bombs. "More and more, there is an actuarial approach to credit analysis rather than the old-fashioned practice of looking each borrower in the eye

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_euoz_2.gif)

1 Comments:

CLO managers essentially buy a bunch of loans arranged by banks, package them together into a pool, and then carve out different securities to sell to investors, taking a fee for their troubles. While the loans they collect are mostly "junk"--meaning they carry low credit ratings--the securities that come from the pool are mostly "investment-grade," carrying high ratings. Ironically, that attracts people seeking the very safest investments.

Post a Comment

<< Home